Zone: Java

Recently I needed to put together some code to perform autowiring of dependencies using Java annotations. The annotation had an optional parameter specifying a name; if the name was missing, the dependency would be wired by type matching.

So of course the core logic ended up looking like:

private void wireDependency(Field field, Class<?> annotation, Object o) {

if (!wireByName(field, annotation, o)) {

wireByType(field, annotation, o);

}

}

This falls under the category of “as simple as possible, but no simpler”. But I would also argue that this is an implementation of the Strategy pattern.

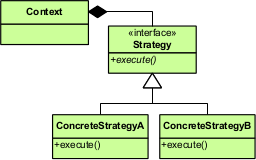

Immediately I sense some objections. The strategy pattern makes the algorithms interchangeable! Strategies should implement an interface and each exist in a separate class, so new ones can be more easily added later! In other words:

That’s all well and good, but it brings me to the title of this article, which is that design patterns are not blueprints. A pattern is a way of thinking about something and a way of communicating about something. To follow the example implementation of a pattern without thinking is as silly as doing anything else without thinking.

In this case, it would be possible to define a WiringStrategy interface with

a wire() method. Then, each wiring type could be a separate class. The

top-level logic could get passed a list of WiringStrategy instances, and work

through each one until one was successful. That way, we could add new ways

of wiring without having to make any changes to the existing logic.

But what would we have saved? We still have to add new code to add a new wiring strategy. And we’d still have to update the list of strategies. (Worst case, we would have really messed ourselves up with softcoding and externalized the list of strategies to a configuration file. Even in that case, we have to update something somewhere.) So the benefits from following the “blueprint” for the strategy pattern seem pretty minimal.

And what do we give up? Before, someone looking at and maintaining this code would see two method calls with obvious purposes, and understand the priority between them. If we shift to separate classes and a list in the name of flexibility, the poor maintainer now has to go multiple places to understand what the code is doing. It just doesn’t seem worth it.

This may seem like a contrived example, but I’ve personally witnessed cases that are this bad. Sometimes it’s the person who is convinced that “magic numbers” in the code are bad, but those same numbers defined as a constant and used once, or loaded from a configuration file and used once, are somehow OK. Configuration files have their place, but when they are packaged with the code and not intended to be updated by the user, it takes just as many steps to update the value in the configuration file as it does to update it in the code. Other times, it’s the person who feels the need to move all object instantiation to a factory, even though the code calling the factory needs to provide all the context necessary to instantiate the object, so there’s really no encapsulation taking place.

At the end of the day, all of our design patterns and best practices are

designed to train our minds so that we write good code. They are not

supposed to be a substitute for thought. The best users of design patterns

don’t have to label their classes AbcFactory or XyzStrategy or

AbstractProxyVisitorImpl because the use of the design pattern is

inherent (and maybe even invisible).

Like the wise programmer says in the Tao of Programming, “Technique? What I follow is Tao – beyond all techniques!”