I’m in the midst of teaching an Introduction to Java class. Like most courses of this type, when I introduce the standard JVM collections I intend to provide guidance on which type of collection to use when.

I wanted to show the real-world effects of making the correct or incorrect decision, so I put together an example. I used the excellent Caliper library to create a class that benchmarks pulling data from existing collections. Caliper is nice for this kind of thing because it does the measurement for you, and automatically handles some things like garbage collection coming in and messing up your test. It also publishes the results to a webapp, with a useful table that I’ll be able to use in my slides. Caliper is undergoing a change to its API at the moment, so I used the old API since that’s the version that’s available in Maven. Both APIs look a lot like JUnit; the old API looks like JUnit 3 and the new API looks like JUnit 4.

The benchmark code is part of my small but growing GitHub repository associated with my Introduction to Java class. The benchmark methods look like this:

public String timeArrayListIteration(int reps) {

String name = null;

for (int i = 0; i < reps; i++) {

for (Person p: personArrayList) {

name = p.getLastName();

}

}

return name;

}

The time at the front of the method name works like JUnit 3’s test —

it marks the method as something that Caliper should benchmark. Caliper handles

choosing a sensible value for reps in order to provide consistent and

meaningful output. The method returns a “meaningful” value so that the compiler

won’t be able to optimize it away.

Of course, there are a lot of benchmarks out there already, but most of them focus on comparing the performance of different collections libraries, or of similar collection types that should have the same Big-O performance. What I was after is showing the dramatic difference of using the wrong collection type entirely (e.g. a list instead of a map).

Is this realistic? It is in my experience. I’ve found and fixed many cases where a list collection was being used even when most users of the collection were doing searches for a specific element. It seems that “data store” classes are susceptible to this kind of thing, especially when they start out with simple append and iteration operations and then progress to include more complex functions.

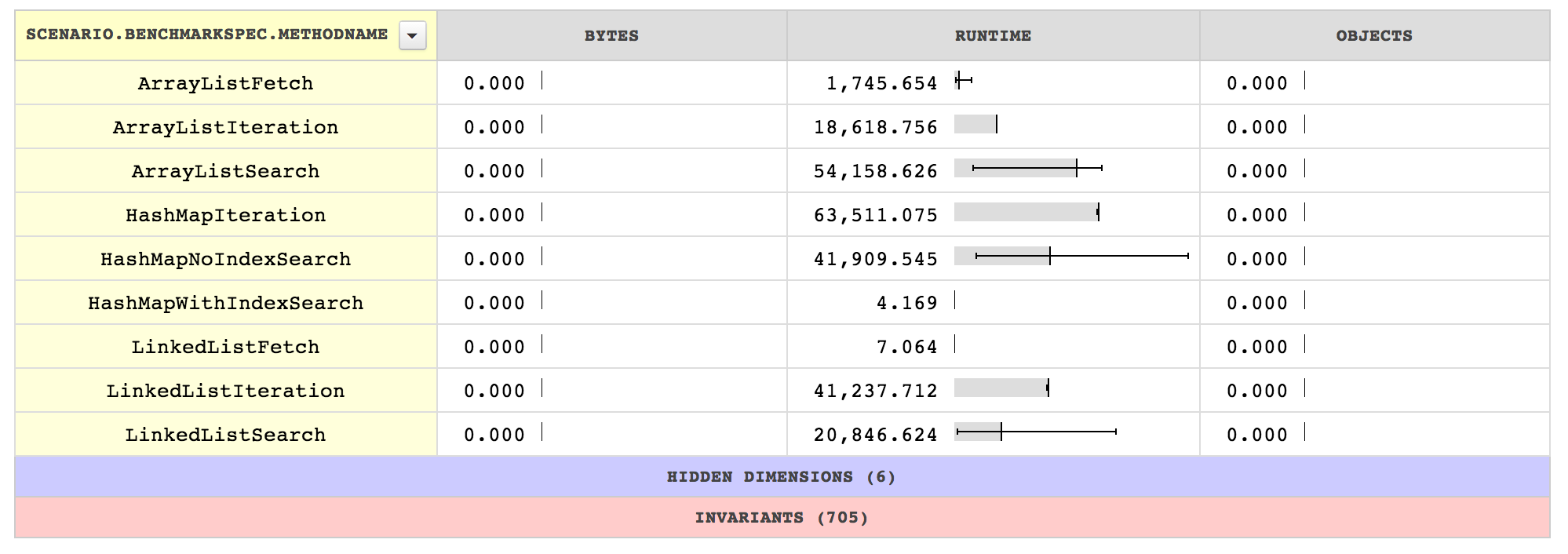

From my simple test, the qualitative ordering of performance is what everyone would expect. It’s painful to iterate over a map’s values. It’s very painful to search a list. What might be at least a little surprising is the size of the difference.

Iteration over a hash map took 3 times as long as over an array list, and 1.5x a linked list. Searching over an array list took 13 times as long as pulling an item out of a hash map when there was an index handy to help.

Note that because I choose to search for a random element, there’s a lot of variance in the searches that have to iterate over the collection. So the displayed number is the average performance under uniform access assumptions.

One other interesting point is the relative performance of array lists versus linked lists when fetching a specific element with a known location. Most people suggest linked lists as the number of elements grows large, and that’s good advice where there will be inserts and deletes that are not at the end. But if the primary use case will be adding things, fetching them, and iterating over them, a large array list may still be noticeably better.

My intent with this code was to scare my students into using the right

collection, so I didn’t spend time on other things I think would be interesting,

like measuring how expensive it is to maintain an extra index on a hash map in

order to avoid a search. These numbers seem to indicate that it would be

worthwhile to spend 10 times the cost of a single search on index updates. Since

updating hash map indices is O(1), that suggests it’s almost always worth it.

It would be interesting to try to verify that.