I was reading Niklaus Wirth’s On the Design of Programming Languages and was struck by his discussion of simplicity. It appeared to me to apply to a number of concepts in architecture and design beyond just programming languages, and even to explain why we so often disagree about design choices.

To start, I want to write about a principle I think is very important for architects and one that has been helpful for me in architecting large systems. By large systems I mean systems that are developed over years and have dozens of developers and dozens of components.

In the defense industry, there is a standard for specifying architecture. It is known, like anything in defense, by an acronym: the Department of Defense Architectural Framework (DoDAF). It consists of a set of views divded into three categories: operational, system, and technical. Within each category are a number of views (which might be diagrams or tables) that show some aspect of the system. (I’m writing about DoDAF version 1, which still seems to me to be in wider use, but other than terminology changes what I’m writing applies to version 2 as well.)

When DoDAF is done correctly, all of the information for the system is contained somewhere in one of the views. And that is exactly why DoDAF, for all its careful organization and categorization of system information, misses out on what I think is an essential element for architects: the one page diagram.

On every job I’ve had as software architect, I saw it as important to create a single diagram that expresses the system concept. No two of these diagrams have looked the same, and they don’t generally obey the rules of a modeling language. The goal, to borrow from Martin Fowler’s idea of “UmlMode”, is to communicate the concepts, not to specify the system.

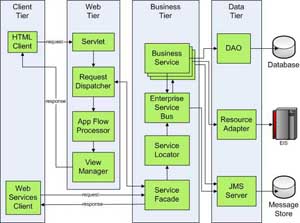

Take as an example this old but good overview of Java EE from a 2008 JavaWorld article:

Anyone familiar with Java EE knows that this diagram leaves out a lot of essential elements (transactions are just one example). And some of the things in that diagram are not key to Java EE (like an enterprise service bus). But someone learning Java EE could keep a copy of that handy and refer to it as they go, and it would serve them well. The one page diagram leverages abstraction and generalization to convey a simple concept in exactly the way Wirth describes in his paper on programming languages.

Per Fowler’s way of organizing, DoDAF is about completeness. Each diagram has a purpose and the overall purpose of the framework is to ensure that every decision about a system is considered and the outcome is recorded. The one page diagram has no place in DoDAF because each DoDAF view is about a specific thing (such as standards used, or traceability of system components to the required behaviors, or state transitions).

Even UML or SysML, which has diagrams that look like our Tomcat diagram above, are not in my view very suitable for the one page diagram, for two reasons. First, in the one page diagram it is usually necessary to “cheat” a little in choosing boxes and showing connections. For example, I like to draw a publish / subscribe messaging framework as a bus even though most frameworks are client / server through a broker. This means that the constructs on the one page diagram might be analogous to functions in the real system rather than an exact representation. By choosing a formal modeling language for the diagram, we risk confusing the diagram user.

Second, modeling languages use diagram elements (markers, associations, multiplicity) that keep the diagram from being completely self-contained. I’m sure there are lots of people who can distinguish between the filled diamond of composition and the hollow diamond of aggregation without looking it up, but this kind of minutae detracts from conveying a simple system concept.

So what makes a good one page diagram? If I knew that for sure, I wouldn’t have so many cases where I struggle to find the right way and end up discarding numerous failed attempts. But where I’ve managed to stumble into good diagrams they’ve had some common features:

- Whiteboard Simple. A one page diagram is going to leave some stuff out, so you won’t be able to use it as-is to discuss every part of the system. If the diagram can quickly be drawn on a whiteboard, you can use it for informal discussions that get into areas that aren’t covered by the “official” version.

- Represents a Story. Another way of saying this would be “Don’t Fear the Narrative.” It should be possible to get some value from a one page diagram just by looking at it, but much more value will come from the description that goes with it, especially if the description is interactive. So it should be possible to quickly walk someone through a diagram using some key feature of the system to show how the architecture works in practice.

- Self Contained and Coherent. If you use different line types, add a legend. If you use colors, add a legend. Don’t leave people wondering if the colors or dashed lines mean something. And any distinctions made on the diagram should be essential to the story, or the diagram will seem busy.

- Printable Size. Ideally it should be letter or A4. Anything bigger will be hard to read on a screen and more complicated to print correctly. One of the best moments of my life as an architect was seeing a one page diagram I created posted on someone else’s wall.

- By Hand, Not By Tool. I love tools like Mermaid that will generate diagrams from text descriptions, but every quality diagram I’ve made was laid out by hand. The structure of the diagram and the relative position of objects matters a lot to how people perceive the diagram, and it is essential not to waste that channel of communication.